The Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR) (OJ. Regulation (EU) 2024/1781) entered into force on 18 July 2024. The new ESPR replaces the previous Ecodesign Directive 2009/125/EC and significantly expands the scope of application for ecodesign requirements, in line with the Commission’s Circular Economy Action Plan of 11 March 2020. The IBA Forum editorial team spoke to environmental law expert Professor Martin Führ from Darmstadt University of Applied Sciences about current and future material requirements, the Digital Product Passport and opportunities for new service-oriented business models in the European Union.

Dr Führ, what is meant by ecodesign?

According to Article 2 (6) of the ESPR, ecodesign “means the integration of environmental sustainability considerations into the characteristics of a product and the processes taking place throughout the product’s value chain”. The ESPR and the ecodesign requirements issued on its basis therefore focus on the entire life cycle of a product — from manufacture to disposal.

How does the new Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR) support the transition to more sustainable products and what long-term effects do you expect for the European market?

The European Commission’s implementing regulations create uniform requirements for all affected product groups. Products may only be marketed if they meet these specifications. Each piece of furniture must also have a Digital Product Passport. The regulation thus creates a level playing field.

Furniture is right at the top of the priority list of ecodesign implementation regulations. What special challenges do you see in the implementation of material compliance requirements for this product group?

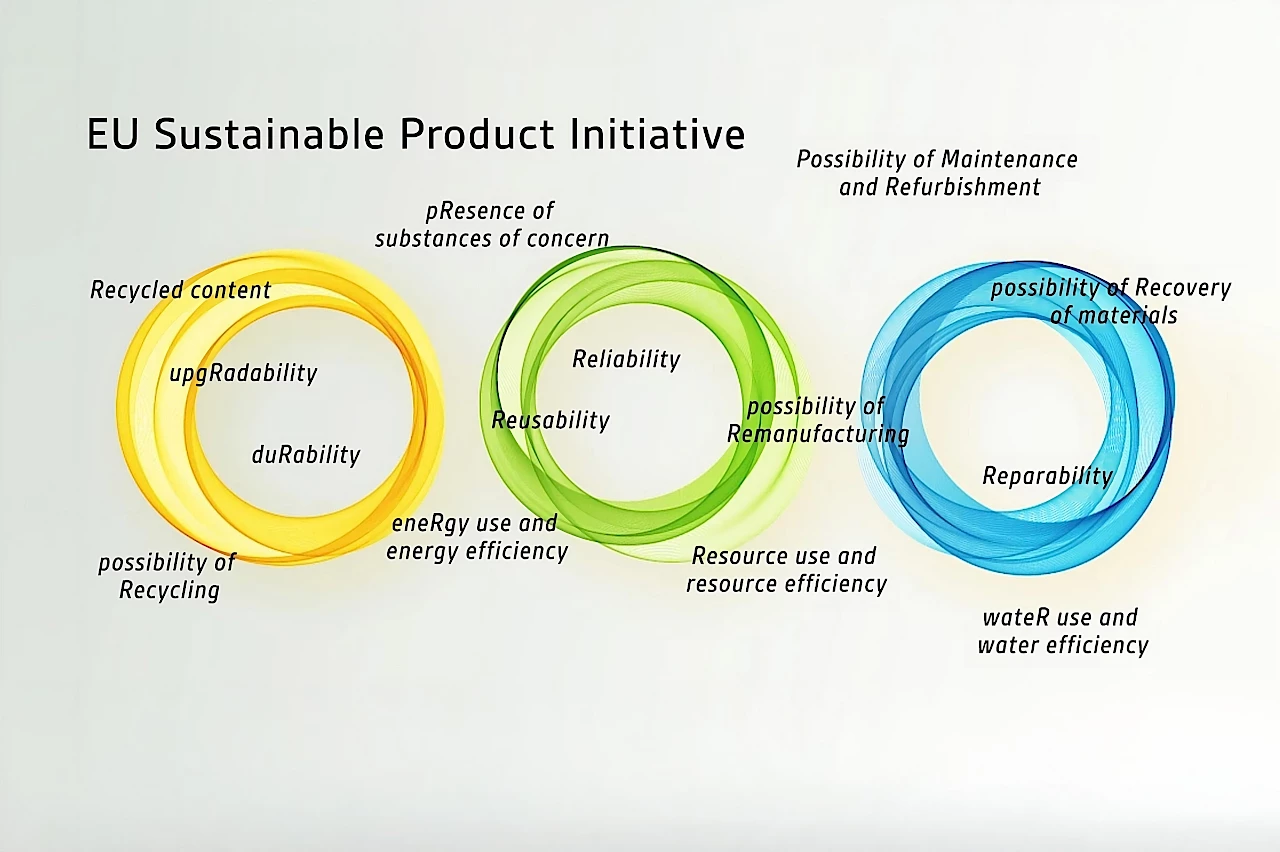

In future, furniture must comply with the R strategies formulated in Article 5 para. 1 of the ESPR:

(a) Durability

(b) Reliability

(c) Reusability

(d) Upgradability

(e) Repairability

(f) The possibility of maintenance and refurbishment

(g) The presence of substances of concern

(h) Energy use and energy efficiency

(i) Water use and water efficiency

(j) Resource use and resource efficiency

(k) Recycled content

(l) The possibility of remanufacturing

(m) Recyclability

(n) The possibility of the recovery of materials

(o) Environmental impacts, including carbon footprint and environmental footprint

That’s not exactly a small number of requirements. It is therefore important to develop methods to specify these performance requirements, store them in the Digital Product Passport and thus enable market transparency.

What role does the Digital Product Passport play and what are the challenges in standardizing this data to ensure that it is trustworthy and up-to-date?

The Digital Product Passport (DPP) is the main communication tool in the supply chain all the way to the end product. The data for the R strategies must be stored in it. It is crucial that the components and their materials are also stored there. The development and design of the products can then be aligned with the R criteria on this basis. Data from upstream suppliers in the DPP is therefore a prerequisite for innovation. To achieve this, product developers must be able to rely on the data being complete and reliable. It must also be ensured that the supplier updates the DPP whenever something changes, for example a change of upstream sub-suppliers with a different carbon footprint or material composition. You therefore need a set of governance rules that contains guidelines and mechanisms to enforce them. All of this must also be integrated into the private-law contracts with the suppliers.

An important aspect of the ESPR is the handling of chemicals in products. What new requirements does this mean for industry, particularly with regard to REACH and RohS?

The requirements from REACH and RohS as such are not new. What this actually means in terms of their practical implementation is not clear to everyone, and not just in the furniture sector. With the DPP, however, there is now an option to ensure material compliance in a standardized form. The traceability of all materials contained in the components is an essential prerequisite for this. Incidentally, this has also been required by No. 8.5.2 of ISO 9000 since 2015. So this is nothing new either.

It would be a serious mistake to limit ourselves to the substances already regulated under REACH and RohS. Such an approach would mean that the entire communication process in the supply chain would have to be rolled out again for every change. REACH is expected to bring continual change: the European Chemicals Agency publishes new substances (SVHC) on its website every January and July. The active reporting obligations under Art. 33 para. 1 of REACH then apply immediately. In addition, new bans and limit values are constantly being added to Annex XVII of REACH. The same applies to electrical and electronic components under RohS. The ESPR will also contain performance and information requirements in this regard, as shown in Annex I (f):

„use of substances, and in particular the use of substances of concern, on their own, as constituents of substances or in mixtures, during the production process of products, or leading to their presence in products, including once those products become waste, and their impacts on human health and the environment […]”

This applies to both the substances used in production and those that are still contained in the components and therefore in the end product.

For the first time, almost all physical products are included in the ESPR. In which sectors do you think compliance with ecodesign requirements has the greatest potential to make a significant contribution to climate change mitigation?

The greatest contribution to climate change mitigation comes from extending the service life of products and their components, because then you don’t have to take any new raw materials from the ground or from forests. As a result, you eliminate all the associated environmental and climate impacts. Accordingly, most of the R strategies also aim to increase the useful life of products. The second priority is to align the manufacturing processes with the criteria of resource conservation and low pollution. Only then does recycling come into play — as letter (m) in the list of requirements from Article 5 ESPR. However, high-quality recycling requires that no problematic materials are kept in the cycle. Traceability of the material composition is also the key factor for this.

Among the product groups that have the greatest potential to contribute to the goals of the ESPR, I actually see furniture in first place. On the one hand, it involves an enormous flow of materials: Around 10 million tonnes of furniture end up as waste in the EU every year. At the same time, there is enormous potential here for reducing the burden on the environment and climate, but also for possible health effects. After all, the vast majority of furniture is located in closed rooms. It is therefore no coincidence that furniture is at the top of the list of product groups for which the European Commission is preparing implementing regulations.

Your ORGATEC presentation also dealt with the possibility of developing new, service-oriented business models through compliance with ecodesign regulations. Can you give examples of how companies can make concrete use of these opportunities?

The new regulations create a changed market environment. The more concretely the R strategies are anchored in the performance criteria for products and the associated information requirements, the greater the market opportunities for business models aimed at maintenance, repairability, retrofitting and the reuse of entire items of furniture or individual components. Having a digital twin of each individual piece of furniture and the most important components makes it possible to order the right spare part or view retrofit options directly from an app. The first companies, for example from Denmark, are already offering this service: You scan the QR code or read the RFID code and can view the piece of furniture in a three-dimensional model and go directly to the ordering options.

This gives component manufacturers the opportunity to deliver directly to the end customer. Companies that refurbish used furniture also find it easier to obtain the right components because all dimensions and other specifications are stored. Thanks to the DPP and its integration into the app, other front colours or technical solutions that were not yet available at the time of initial marketing can be identified and ordered with a click.

How do you assess the overall impact on the furniture sector?

Overall, the ecodesign regulations significantly increase the quality requirements for products. In conjunction with the transparency requirements in the DPP, the market environment is changing considerably. The new regulation represents a departure from the strategy of bringing more and more furniture onto the market at ever lower cost (but with increased use of resources and release of greenhouse gases). Instead, it favours business models along the lines of R strategies and a product design geared towards them, combined with service offerings.

Many of the life-extending R strategies also require offers in the respective region. For logistical reasons alone, it makes no sense to transport the products over long distances. The new business models are therefore generated where the furniture is located.

All companies that set themselves ambitious quality and transparency targets thus have a market advantage. Forward-looking entrepreneurial action is therefore required: Internal processes and supplier relationships must already be aligned with the foreseeable requirements. Traceability is an indispensable prerequisite for this and at the same time is the main enabling factor for all business models aligned with ecodesign requirements. Creating the technical and organizational prerequisites for this, but above all the rules of the game in terms of a governance framework, is the order of the day.

Dr Führ, thank you for this interview.

Prof Dr Martin Führ, born in 1958, has been Professor of Public Law, Legal Theory and Comparative Law at Darmstadt University of Applied Sciences (h_da) since 1995. He heads the master’s programme “Risk Assessment and Sustainability Management” (RASUM) and the special research group Institutional Analysis (sofia) and is involved in the project “System Innovation for Sustainable Development (s:ne)”. He completed his PhD and habilitation at the Goethe University Frankfurt/Main (“Eigen-Verantwortung im Rechtsstaat”, Berlin 2002). At Öko-Institut e.V., Freiburg/Darmstadt/Berlin, he headed the legal department for many years; from 1993–1997 he was a member of the board. From 2008 to 2015, he was a member of the Management Board of the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA, Helsinki), appointed by the European Commission. The German Bundestag’s Committee of Inquiry into the “diesel scandal” formally appointed him as an expert. He is specialised in substance and product law, industrial plant law and environmental impact assessment. He is the editor of the Community Commentary on the Federal Immission Control Act and the REACH Practical Handbook. His publications cover the entire spectrum of economic administration and environmental law, as well as the legal framework for sustainable development and economic analyses of the law. Further information at: fbgw.h‑da.de.

Photo credits: Illustration based on © ‑strizh-/iStock