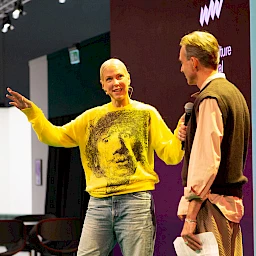

During the Work Culture Festival, trend researcher Birgit Gebhardt and perception psychologist Dr Axel Buether discussed the question of what role spaces play in connection with our experiences, our productivity and our health, and why the physical office needs to catch up in this regard. The discussion focused on the realization that our perception of spaces is determined by our senses, which react permanently to our surroundings and, through the quality of our relationship with these surroundings, also define how we perceive a space. Space is thus not a neutral realm but rather actively shapes our daily lives.

Three types of spaces

Gebhardt and Buether differentiate between three central dimensions of spaces: the sensory space, the perception space and the social space.

the Sensory space: The sensory space describes how our biological senses perceive the surrounding environment.

the perception space: The perception space is the mental construct that we create from these sensory impressions.

the social space: The social space is created from the relationships that we experience and perceive in a space.

These levels are closely interwoven with one another. Their interplay makes it possible to explain how spaces influence our behaviour—and to determine which requirements modern offices need to meet.

The sensory space: biological foundations

Humans are daytime creatures whose perceptions are largely shaped by their sense of sight. Around 70% of our sensory impressions are processed visually, while the senses of smell, sound and touch serve as supplementary sources of information. Spaces are therefore primarily defined visually—we orient ourselves by means of light, colours, shapes and movements. A lack of daylight, monotonous surfaces or insufficient visual differentiation quickly lead to fatigue and a reduced ability to concentrate. Light in particular plays a key role here, as it controls our hormonal balance and has a direct impact on our alertness and mood. The goal of human-centric lighting projects is to replicate as precisely as possible the qualities of natural daylight. A high proportion of blue light during the midday period promotes alertness and concentration, while warmer light colours later on support regeneration through relaxation. The decisive factor here is the use of dynamic light adjustment in line with the natural course of the day. According to Buether, well-being, health and performance can only be maintained over the long term if lighting, colours and other sensory impressions are aligned with our biological processes and requirements. An office that ignores these aspects offers more favourable conditions for chronic fatigue and stress.

Rhythm of activity and recovery

Studies show that people only work in a highly productive manner for around 30% of the time every day. Productive work is therefore not so much a question of duration as it is a matter of finding the right rhythm. Here, Buether referred to the concept of mini-breaks—around 25 minutes of focused work followed by a five-minute break—and also talked about the use of longer recovery cycles. After around two hours, one should deliberately look off into the distance in order to relieve the strain on the eyes and relax their muscles. Creative impulses often do not arise during periods of maximum concentration but in a state of reduced attentiveness—and sometimes in “daydreaming mode”. Walks, carefully and consciously designed break rooms, and informal interaction zones can help create such states. With regard to office design, this means that offices should not only maximize spatial efficiency but also offer spaces that support different types of activities—from focused work to regeneration or playful experimentation. Only through such alternation can a work environment be created that enables efficiency and consistent performance over the long term.

The perception space: a construct of the brain

Spaces are not objective structures but rather a mental construct of our brains. Sensory impressions are permanently filtered, interpreted and compared with experiences. This gives rise to subjective realities. It explains why look at green spaces calms or why monotonous, bland surroundings have a tiring effect. Spatial design that is aligned with human needs therefore involves a lot more than providing rooms and spaces. It also takes into account visual and haptic qualities, acoustic conditions, atmospheres and outlooks. Offices that are designed merely on the basis of normative grid plans or square-metre requirements will be considered inadequate from this point of view. Spaces that take perception into consideration, on the other hand, are like an instruction manual for behaviour. They proactively invite occupants to perform certain activities, facilitate orientation, and create clarity so that work is not just completed but also completed productively and in a healthy manner.

Digital enhancement and cognitive surroundings

Technological innovations are increasingly enhancing our perception space. Virtual reality headsets, noise-cancelling headphones and AI-based systems all have a direct effect on sensory organs and create new levels of reality. Researchers refer to these as cognitive environments—spaces that use sensors to react to signals from humans and create feedback. However, Buether also pointed out that digital tools cannot replace the physical realm. Instead, it makes sense to develop a portfolio of tools, as Buether believes that digital enhancements are only useful for certain tasks such as training and remote collaboration. The physical dimension of human perception remains essential. The important thing is to ensure that physical spaces continue to offer sensory stimuli—for example in the form of lighting, colour, acoustic and haptic sensations. This is the only way to make productive use of the interplay between natural and digitally enhanced perception.

The social space: relationships in the office

Along with the sensory space and the perception space, the social space also plays a key role in the working world. People are social creatures and our brains are designed to experience various types of contact and changing interactions. Studies show that groups of up to 30 people are ideal for maintaining stable social relationships, which is a much higher number than what one can experience when working from home, for example. An office that has been reduced to a series of functional workstations also cannot achieve this dimension of interaction. Good office design makes it possible to alternate between focused work and collaborative work phases. This requires visible and attractive structures—everything from lounges to retreat spaces and zones for interaction. The relationship between the front stage and back stage is particularly important here, as employees need both spaces in which they can present themselves and also protected spaces in which they can remain completely relaxed and unobserved. Such retreat spaces must be designed to be appealing in terms of people’s perceptions and senses; otherwise they will not be used. The social space thus makes an important contribution to ensuring that emotional relationships can develop between co-workers, and also between employees and their workplace. Only when this dimension is also taken into account can an office environment be created that is productive, healthy and attractive over the long term.

Recommendations for companies

The discussion led to the identification of several approaches for the further development of physical work environments:

- Create an atmosphere marked by sensory diversity: avoid monotony; make use of different materials, colours and lighting atmospheres and moods.

- Take biorhythms into account: design lighting in line with the natural way in which a day proceeds and in a manner that supports the alternation between activity and regeneration.

- Allow spaces for creativity: create zones that enable daydreaming, informal conversations or changes of perspective.

- Take perception seriously: plan spaces not only in a normative manner but also taking into account the impact these spaces will have on people’s mental state and behaviour.

- Strengthen the social dimension: design offices to be places for maintaining and nurturing relationships—with clearly identifiable retreat areas and zones for interaction.

- Use digital tools to supplement other measures: technology should be used to enhance physical spaces, not replace them.

The physical office is not about to become obsolete but is instead a resource whose potential has yet to be fully exploited. Spaces have an effect on our senses, shape our perception and determine the quality of social relationships. The office of the future will therefore need to design the three levels purposefully—i.e. as a sensory space that is aligned with our biological processes and requirements, a perception space that offers sensory stimuli, and a social space that promotes the development of relationships. Only then will it be able to keep up with future developments and become a place that not only enables work to be performed but also promotes and strengthens health, creativity and a sense of community.