Architect and researcher Dr Claude Dutson spoke at the Work Culture Festival about the special architecture in Silicon Valley and its importance for the collaboration, innovation and corporate culture of the tech companies based there. Among other things, she discussed how architectural design can specifically promote moments of serendipity and productive encounters.

Architecture as a catalyst for creativity

Silicon Valley is not only synonymous with technological innovation, but also a place where working methods and architecture are inextricably linked. The buildings of Apple, Google (Alphabet) and Meta are deliberately designed to support creativity and interdisciplinary collaboration. It’s not just about large, open workspaces, but also about subtle architectural elements that encourage spontaneous interaction. The concept of serendipity — the fortunate coincidence — plays a key role here. Pathways, communication zones and multipurpose areas allow employees from different departments to accidentally meet and talk to each other. These chance encounters are seen as a driver of innovation, often leading to new ideas and synergies.

From a closed office to an open innovation environment

The architecture of technology companies has changed significantly over the decades. While the first company buildings in Silicon Valley were still characterized by closed rooms and classic office structures, the picture changed with the dotcom boom of the 1990s. Companies began to integrate leisure facilities into their buildings in order to make the workplace more attractive and increase employee loyalty to the company. However, today’s corporate headquarters are far more than just places of work with additional amenities. They are consciously designed experiential spaces that reflect the corporate culture and philosophy. In her presentation, Dutson introduced various design approaches used by leading tech companies:

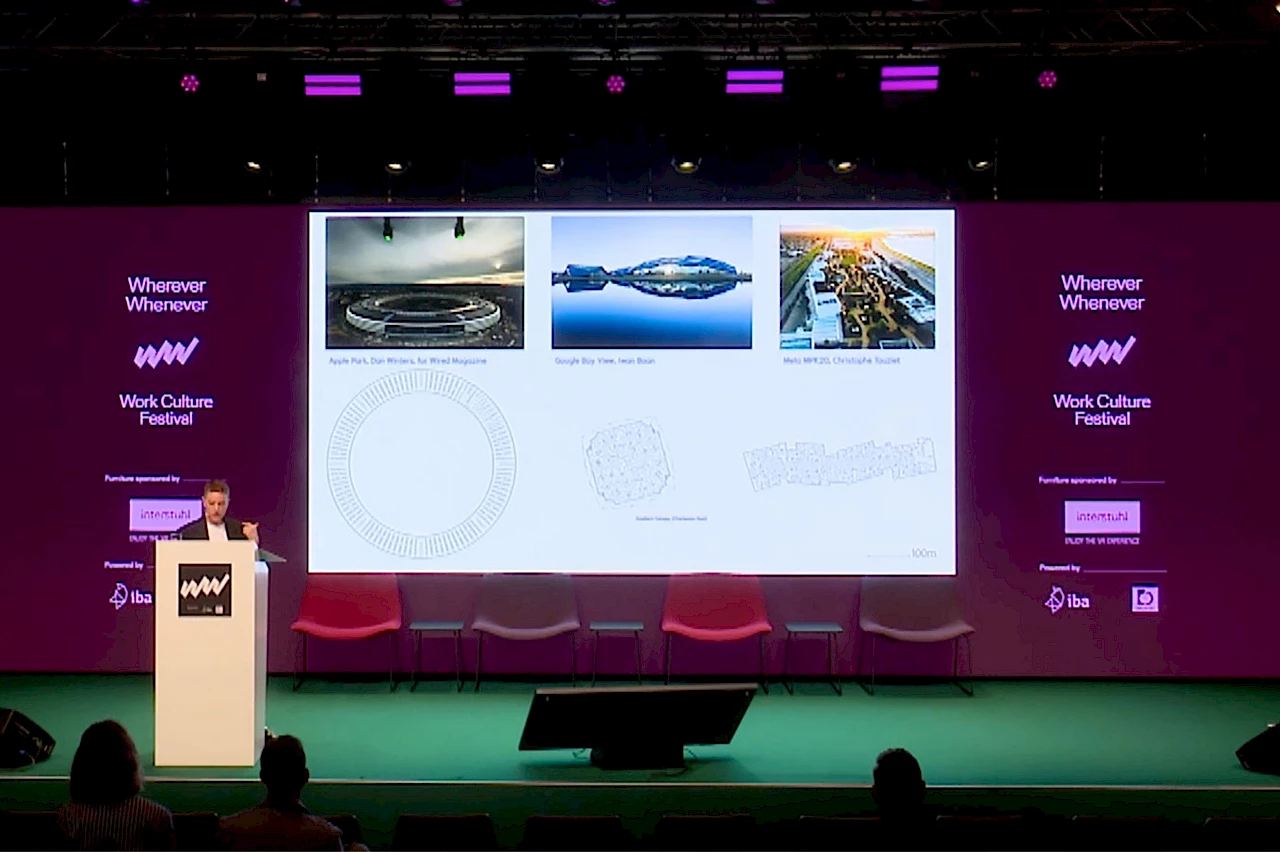

- Googleplex (Alphabet): One of the first concepts to use the design of outdoor spaces as an extension of the workplace. The campus promotes creative breaks in a natural environment.

- Facebook (Meta) – MPK20: A 40,000-square-metre open-space area that radically implements the concept of open collaboration.

- Apple Park: A circular main building that ensures that every location within the complex is within walking distance and encourages spontaneous interaction.

Architecture as a vehicle for identity

In addition to functionality, identity formation also plays an important role in the architecture of Silicon Valley. Using photos and 3D reconstructions, Dutson showed that elements in the company buildings are not randomly placed, but have a deeper meaning. For example, Google’s Moonshot Factory (X) contains prototypes of earlier projects such as drones or balloons from the discontinued Loon Project. These objects not only serve as decoration, but also remind employees of visionary ideas and the experimental nature of the corporate philosophy. Architecture thus becomes a medium that makes corporate values and innovative spirit visible.

Apple and Meta are also pursuing similar concepts. Apple’s main building reflects the perfection and attention to detail that the company also strives for in its products. Every element is precisely planned—from the arrangement of the offices to the choice of materials. Meta pursues a completely different strategy with its open, adaptable office spaces. The buildings are deliberately kept flexible so that they can be adapted to new team structures or innovation projects. This promotes the idea of a “hack culture” in which creative problem-solving and iterative processes take centre stage. The architectural design thus becomes a direct expression of the respective corporate philosophy.

Silicon Valley architecture as a global model?

In her presentation, Dutson also raised the question of whether the specific architectural concepts of Silicon Valley are transferable to other companies and sectors. It became clear that many of these concepts are strongly interwoven with the corporate culture, financial resources and historical development of the region and therefore cannot be easily transferred to other contexts. Nevertheless, certain principles, such as the promotion of serendipity or the design of flexible working environments, can also be useful in other sectors. A key point here is that the architecture of the tech giants is tailored to a work culture that is characterized by a high level of identification with the company and a fusion of work and private life. This can be more difficult to implement in other sectors, especially in more traditional corporate structures. Nevertheless, elements such as open meeting zones, modular room concepts and informal work areas can help to improve communication and the ability to innovate in companies. Urban planners can also learn from these concepts.

Dutson’s conclusion is that architecture is not just functional or prestigious—it can be understood as an active creative force that has the potential to catalyse innovation processes and sustainably shape the creative exchange in companies, thus influencing not only the way organizations work, but also their success in the long term.