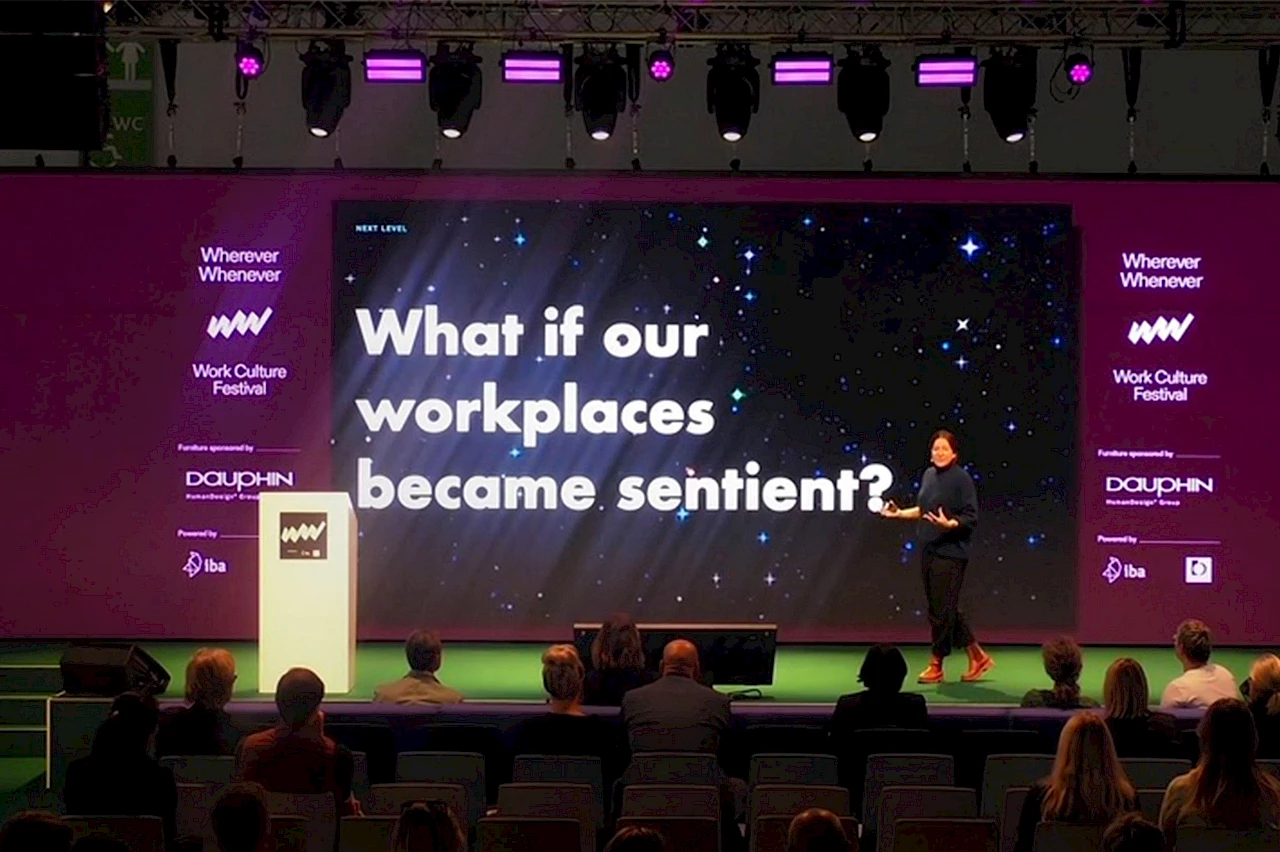

“Technology will move off the screen and become the invisible engine that powers the real world around us.” Sophie Kleber, UX Lead at Google and expert in ethical AI and future human-machine interaction, opened her keynote speech at the Work Culture Festival with this vision. Her presentation outlined how artificial intelligence (AI) is changing not only the way we work but also how our working environments are being designed as we move towards what are known as neuro-adaptive spaces—spaces that respond to our needs and actively increase our well-being.

From rigid offices to empathetic spaces

Kleber painted a picture of a working world in which spaces actively adapt to the needs of their users. This is made possible by smart, sensor-based systems that use light, temperature, air quality and other parameters to dynamically shape the working environment. This turns the workplace into an empathetic companion that supports productivity and relaxation in equal measure. But it’s not just about technical sophistication, it’s about a fundamental change of perspective: Spaces thus become active players in everyday working life. They register moods, recognise stress levels and support individual well-being through targeted adjustments. Anyone entering such a space should not just work. He or she should immediately feel welcome, be inspired and find the right atmosphere for concentrated work, creative collaboration or targeted relaxation. The use of AI and networked systems is creating a new type of working environment that is adaptive, forward-looking and human-centred. These spaces react not only to external conditions, but also to the emotional and cognitive state of their users. It’s a real paradigm shift.

Building blocks of a smart working environment

A key theme of Kleber’s presentation was the importance of specific spatial factors for emotional and cognitive well-being.

- Lighting: natural daylight is the strongest factor influencing well-being. Adaptive lighting systems that take the circadian rhythm into account ensure activation in the morning and relaxation in the afternoon.

- Biophilia: bringing nature into the office, whether through plants, walls of greenery or views of the outdoors, reduces stress, promotes creativity and boosts the feeling of belonging.

- Colours: colours not only have a mood-enhancing effect, but also specifically support cognitive processes. Strong colours such as orange can be stimulating, while blue promotes calm and concentration. Colours also serve as a branding element to anchor a company’s identity into a space.

- Air quality: fresh, clean air is essential for concentration and well-being. Today’s building technologies continuously monitor air quality and ensure a healthy working environment.

- Temperature: comfortable temperatures vary from person to person. Neuro-adaptive spaces recognise these preferences and adjust the climate automatically—a significant contribution to increasing comfort and performance.

- Soundscaping: instead of distracting background noise, smart audio systems create targeted soundscapes that promote concentration or support social interaction. This also includes the deliberate use of acoustic islands for deep work or creative collaboration.

- Scent design: scents have a big influence on emotions and the ability to concentrate. Whether invigorating aromas to increase alertness or calming fragrances for relaxation, targeted scent design can permanently improve the working atmosphere.

The personality of space

Another aspect of Kleber’s presentation was the concept of the personality of space. Spaces are no longer seen merely as static shells, but as empathetic environments with their own character and targeted opportunities for interaction. These spaces do not feel in the literal sense, but they react sensitively to the physical and emotional states of their users. A room can have a calming and protective effect like a cocoon, equipped with soft light sources, subdued colours, soft materials and pleasant fragrances that convey a sense of security and invite you to relax. In another situation, the same room can be transformed into an inspiring workshop in which vibrant colours, invigorating aromas and a stimulating lighting mood provide creative impulses. A room can also be designed as an open, communicative forum with flexible furnishings, clear lines of sight and an inviting soundscape.

The necessary change in the planning process

According to Kleber, this vision requires a radical rethink of the real estate and planning process. Instead of viewing architecture as a self-contained discipline, people and their changing requirements need to consistently take centre stage. Buildings should not be conceived as rigid structures—the need to be flexible, adaptive and adjustable in order to do justice to the dynamic world of work. The change begins with the active involvement of users: Workplace surveys and continuous feedback become a management tool for understanding the actual requirements. It’s not just about room sizes or furnishing, but also about whether employees feel emotionally comfortable and whether there are enough places to retreat and meet.

The physical design also corresponds to this new way of thinking: furniture becomes modular, rooms convertible, from a retreat in the morning to a creative space in the afternoon. Technologies such as mobile partition walls, adaptive lighting and air-conditioning technology and smart control systems enable a flexible use of space. The actual building only comes at the end—sustainable, user-oriented and designed for long-term changeability. The classic linear process of plan—build—furnish—finish is giving way to an iterative process: “We need to think of workspaces like software—as systems that are constantly evolving and adapting,” says Kleber. Property is thus becoming a dynamic value-adding factor and is no longer viewed as a rigid investment object; adaptability and continuous improvement are becoming the key success factors for sustainable working environments. This change requires close cooperation between architecture, technology, HR and company management. Only if all areas work together to create a more humane and adaptable working environment can the full potential of neuroadaptive spaces be exploited for the people who use them every day.

The workplace as an active partner

The end result is a vision of a working environment that is not only functional, but that actively develops human potential. Neuro-adaptive spaces accompany people throughout the working day, support productive phases, enable targeted relaxation and promote a sense of security and belonging. The space acts as an invisible partner that recognises the individual needs of its users, reacts to them and thus actively contributes to health, creativity and efficiency.

Adaptivity goes far beyond technical gimmicks. Neuro-adaptive spaces are an expression of a new attitude: The workplace is seen as a living organism that interacts with its users, understands them and actively supports them in developing their potential. Sophie Kleber concluded her keynote speech with a quote that summed up this paradigm shift: “Responsibly optimised neuro-adaptive architecture has the potential to elevate civilisation to its most human level.” This message made it clear that the future of the working world isn’t more technology, but the smart, empathetic design of our physical environment— an environment that serves the people, their needs and their potential.